By Pratik Chougule, Mick Bransfield, and Solomon Sia

In its proposed rule on events contracts, the CFTC issued a strong denunciation of war markets, but explicitly opted not to define war.

This makes little sense to us.

Without a definition of war, event contract platforms will have little guidance on whether they can offer markets related to a wide array of current events.

In many of the most consequential conflicts in the world, it is unclear whether a war is even occurring.

Proposing a clear, narrow definition of war would help mitigate the possibility that a CFTC-regulated market would create a financial incentive to carry out an act of war.

The CFTC, as an example, could define war as a type of conflict that could only be initiated by designated leaders of a country through formal, defined government processes. It is highly unlikely that political figures’ decision-making at this level would be motivated by an opportunity to profit illicitly from a small investment in a DCM, in which they are not permitted anyway.

The proposal does not sufficiently consider that event contracts related to war could be designed in ways that would be highly beneficial to the public interest as information sources and decision-making instruments, without meaningful perverse incentives.

For example, migrant flows driven by international conflicts are a source of economic risk. It is difficult to see how an event contract on a question like the number of refugees entering a country would create incentives for market participants to carry out a “heinous act” in this domain, much less how they would act on these incentives. Yet these contracts would facilitate price basing, hedging, and other useful information in furtherance of the public interest. We assume this is why the Commission already permits Kalshi to offer a contract on the number of “credible fear” asylum cases.

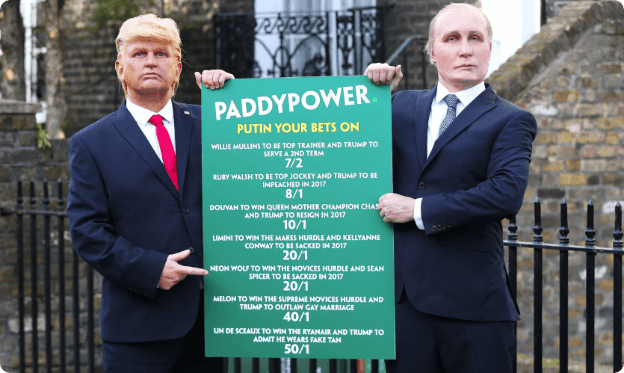

The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine illustrates the above dilemmas. Whether or not the conflict had escalated into a “war” was a matter of debate in the early years of the conflict when Russian president Vladimir Putin referred to the country’s intervention as a “special military operation.” Event contracts could have been offered on the question of when, if ever, Russia or an international body would refer to their intervention in Ukraine as a “war.”

Furthermore, as a consequence of the conflict, there are public interests at stake in questions such as how long Putin, Ukrainian president Vlodymyr Zelensky, and other influential world leaders in the conflict will remain in power, and how many refugees from Russia and Ukraine will enter neighboring countries.

The Commission should offer guidance on the definition of “war” and the type of events that can be offered without running afoul of the rule’s prohibition on war, terrorism, and assassination markets.

We also urge the Commission to clarify that event contracts related to political leaders’ tenure in office would not be prohibited due to the Commission’s opposition to terrorism, war, and assassination markets.

Event contracts on when and for how long political leaders will remain in office are highly pertinent to the public interest. In the vast majority of cases, political leaders leave office due to factors incidental to war, terrorism, and assassination. At the same time, these factors could impact the length of any political leader’s exit—a reality traders in these markets need to consider even if they are difficult to quantify.

We are concerned that overzealous regulators will categorically ban event contracts on political leaders’ tenures in office on the grounds that they might create perverse incentives related to war, terrorism, and assassination.

To that end, the Commission should clarify under what circumstances, if any, political leader markets would run afoul of the rule’s prohibition on terrorism, war, and assassination markets.

Pratik Chougule (@pjchougule) is the executive director of the Coalition for Political Forecasting. Mick Bransfield (@mickbransfield) is the research director of the Coalition for Political Forecasting. Solomon Sia (@sia_solomon) is a board member of the Coalition for Political Forecasting.

This blog post is adapted from the authors’ August 2024 comment letter to the CFTC.